Author's note: The following is from a talk I gave at a Libertarian Party of California convention in Fresno on Jan. 28. Although it is 90-percent faithful to the talk, I rewrote it to reflect further thoughts I had after the speech.

As well as being a research fellow at the Hoover Institution, I'm an economics professor at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey. My students are military officers. After 15 years of teaching there, it occurred to me that I should actually think about what my students do – in other words, think about war. What wars should our government get into, what should U.S. foreign policy be, etc.?

I'm sure that many of you are familiar with the libertarian-designed "World's Smallest Political Quiz." Let me ask you a question: How many questions does that quiz have on foreign policy? [Someone in the audience answered, correctly, "Zero."] We libertarians have honed our principles and applied them to literally hundreds of domestic policy issues. We've done a great job. The depth of our understanding of how to apply our principles to these issues and of the importance of peace in the domestic realm is truly something for us to be proud of. But we haven't given nearly the same care to examining foreign policy.

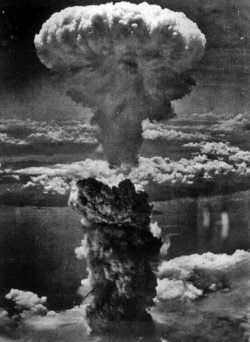

Even our language reflects the relatively primitive state of libertarian thinking about war and foreign policy. I don't know many libertarians who, in talking about the 1993 Clinton tax increase, say, "We raised taxes." They're much more likely to say, "Clinton and Congress raised taxes." In other words, they put the responsibility on the people who acted. But I frequently run into libertarians who will say, without the slightest hint of irony, "We bombed Nagasaki" or "We went to war with Iraq." In other words, they switch from the clear, clean language of individualism that they use in discussing domestic policy to the dark, obfuscatory language of collectivism in discussing foreign policy.

But certain principles apply to government action, and those principles don't become irrelevant in the government's dealings with the people of other countries. It's important, for example, that a government not kill innocent people, whether they are in the country that that government governs or in another country. I would say more, but I want to move on to other issues.

Let's look at the economics of foreign policy and analyze foreign policy the same way economists analyze domestic policy. Consider how we economists analyze price controls on gasoline. We point out that even if the governments that impose price controls on gasoline don't want to cause a shortage of gasoline, the result of a price control that is below the free-market price is a shortage that leads to lines for gasoline. In figuring out the effect of the price control, we don't look at the government officials' intentions – their intentions are irrelevant to understanding the effects of a price control. Indeed, so often do economists find that various policies cause negative unintended consequences that in my "Ten Pillars of Economic Wisdom" that I hand out to students the first day of class, pillar number six is "Every action has unintended consequences."

Similarly, in foreign policy, governments do things that have unintended consequences. Take the Middle East. Please. The takeover of the U.S. embassy in Tehran by a number of Iranians in November 1979 came as a total surprise to most Americans, including me. But that's because neither they nor I had paid much attention to what the U.S. government had been doing in that part of the world. Indeed, the U.S. president at the time, Jimmy Carter, actively discouraged Americans from thinking about past government policy toward Iran, referring to it as "ancient history." But the history wasn't ancient, unless Carter had a young child's view of time. In 1953, the CIA's Kermit Roosevelt and Norman Schwartzkopf Sr. helped overthrow the democratically elected leader of Iran, Mohammed Mossadegh. [See Sheldon Richman, "'Ancient History': U.S. Conduct in the Middle East Since World War Il and the Folly Of Intervention," Cato Institute, August 1991.] Now, Mossadegh was no good guy: he had nationalized some oil companies. But does a government's theft of property justify its overthrow? While few Americans ever knew about the CIA's role in overthrowing a democratic government, many Iranians did, just as if an Iranian government agency had overthrown our government, many Americans would remember. So the takeover of the U.S. embassy was an unintended consequence of the CIA's action in 1953.

Raed On

No comments:

Post a Comment